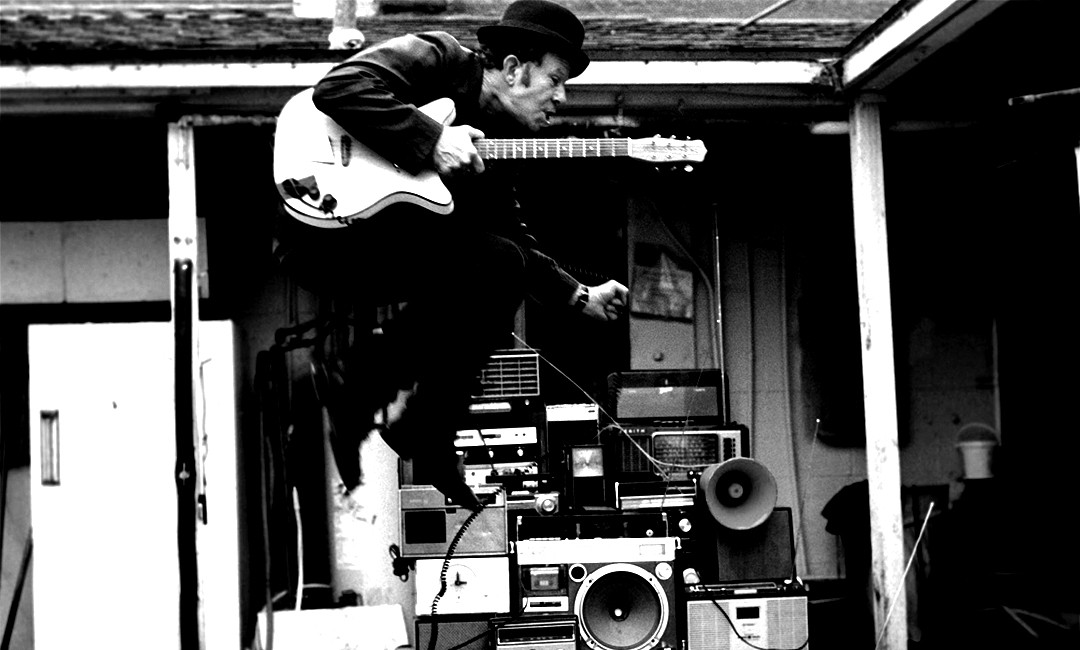

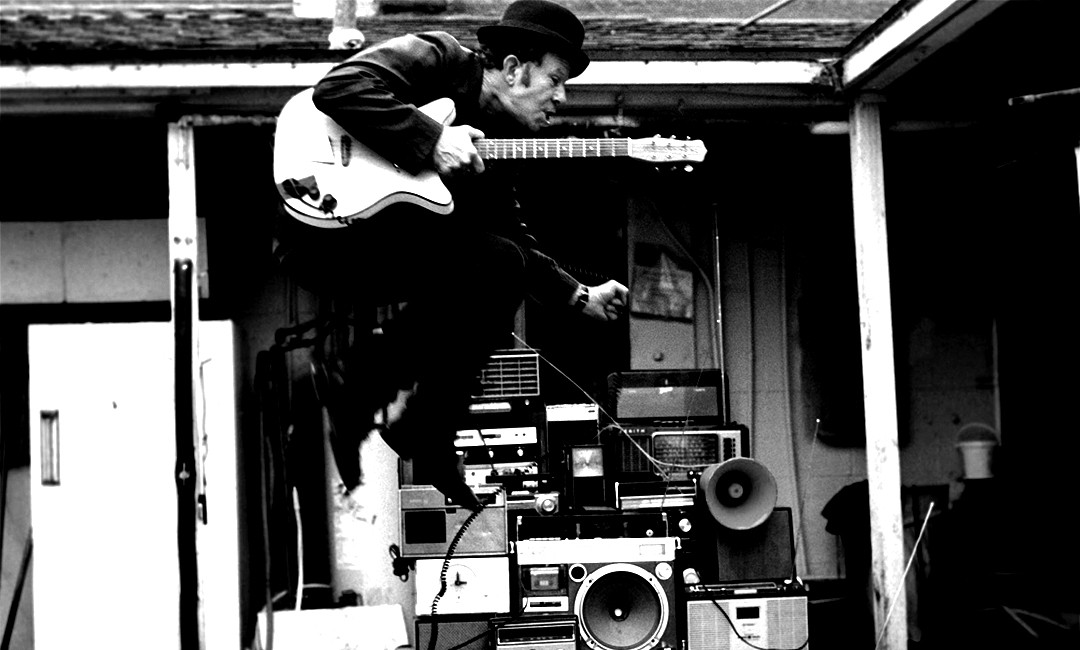

by Cwe | Mar 18, 2016 | Creative Process, Music

Creative Process x Tom Waits

Be ready to let it go when it vanishes. If a song “really wants to be written down, it’ll stick to your head. If it isn’t interesting enough for to remember, well, it can just move along and go get in someone else’s song.”

“Some songs,” he has learned, “don’t want to be recorded.” You can’t wrestle with them or you’ll only scare them off more. Trying to capture them sometimes “is trying to trap birds.” Fortunately, he says, other songs come easy, like “digging potatoes out of the ground.” Others are sticky and weird, like “gum found under an old table.” Clumsy and uncooperative songs may only be useful “to cut up as bait and use ‘em to catch other songs.” Of course, the best songs of all are those that enter you “like dreams taken through a straw.’ In those moments, all you can be, Waits says, is grateful.

“Children make up the best songs, anyway,” he says. “Better than grown-ups. Kids are always working on songs and throwing them away, like little origami things or paper airplanes. They don’t care if they lose it; they’ll just make another one.” This openness is what every artist needs.

by Cwe | Mar 17, 2016 | Creative Process, Creativity, Design, Sneaker

They say three’s the magic number, and for Nike, the design collective of Hiroshi Fujiwara, Tinker Hatfield, and Mark Parker has been pushing the brand forward since its inception in 2002 under the sub-brand HTM.

The first project the trio—made up of a long-time Nike collaborator, the Vice President of Design and Special Projects, and the company’s CEO—created together was their own take on the Air Force 1. That idea might seem commonplace nowadays, but it was something new at the time. Fujiwara, Hatfield, and Parker would later go on to work on niche products such as the Air Moc Mid, Zoom Macropus, and Air Woven before introducing the breakout Flyknit to the world in 2012.

What differentiates the HTM projects from the rest of the trio’s work isn’t just the numbers in which it’s produced: It’s a subversive approach to sneaker design for the largest footwear brand in the world. There are times when Fujiwara, Hatfield, and Parker recreate older product, but their main focus is on crafting things for the future. A perfect example would be the Nike Sock Dart, which first released in 2004, only finding success when it re-released a decade later.

HTM was meant to be a meeting of the minds where the three guys could get together, put aside their regular work, and create something fresh that would be innovative for Nike. Their names alone can help sell the product, but that’s not the intention of HTM, since most of the sneakers made are done so in limited quantities. Instead, they’re here to change the way we look at shoes, even when they’re creating short runs of sneakers for the likes of Kobe Bryant, or hybrid footwear that defies categorization.

To get a better scope of how and why they work together, we spoke to Fujiwara and Hatfield, with quotes from Parker provided by Nike, about their design process and more.

In your words, what is HTM?

Mark Parker: HTM represents a few things for me. First, it’s a place to play and explore new concepts. I love design, so it’s important for me to have a creative outlet. In my role, I travel a lot and connect with a number of cultural influences. HTM is a way for me to put those experiences into something that can be shared with other people. I also just really enjoy the process of working with other talented, creative people. There’s great power in bringing diverse points of view together. It can be incredibly stimulating. We also have a lot of freedom to work without the expectations of commercializing something and, as a small team, we can execute incredibly fast.

More generally, HTM can be a source of inspiration for the broader design teams. At times, we have pushed the edges on new ideas for the company. We introduced woven—which I think surprised a lot of people. We were at the forefront of using knit technology with the Sock Dart. And we introduced Flyknit technology with a pack of HTM shoes that really highlighted what the new process could do aesthetically.

What was the expectation when you started to work together?

Tinker Hatfield: It seemed like an opportunity to sub-brand exclusive and interesting products, kind of in lockstep with our Sportswear division, which was starting to really hum at the time. Some of the early projects for HTM were reinterpretations of preexisting designs. We have also done that more recently. But the conversations that I remember were about how the HTM sub-brand was an opportunity to introduce new ideas, not just re-issued and remade retros. That’s why we introduced Flyknit to the the world through the HTM sub-brand. It was a tidy, easy way to introduce a new technology. We expect to reinterpret some classics and do so in our own way, in a collaborative way, where we all might contribute to one project. More recently, we’ve taken that same approach, where Hiroshi has done a sneaker, Mark has done a sneaker, and I’ve done one, too. We also take a look at the latest technologies and decide the best way to introduce a new idea to the world is through this smaller, more intimate lens of HTM. That’s the way Flyknit got introduced and some other things. We’re open to a lot of different approaches to make things special and unique and more exclusive, but sometimes, maybe, we can do large numbers as well.

Whose idea was it to start HTM?

TH: I can tell you that I don’t remember if it was anyone’s specific idea. It possibly was Mark’s, because me and him would travel to Tokyo and we got to know Hiroshi. He was doing a lot of cool stuff there. He was an influencer and still is today. We all got along and it was fun to run around town with him. He showed us a lot of cool stuff. It seemed like we could all work together. Maybe it was mutual, or maybe it was Mark’s suggestion. I’m not certain.

Did you ever think it was going to become a buzzword associated with sneakers or did you just want to make cool stuff?

TH: I think the latter. We were going around some of the larger business decisions that are made at a company this size and making some more personal creative decisions apart from all of the big business. The three of us would get together and say, “Hey, let’s try this.” It’s quite liberating, and it’s a lot of fun. It was done to develop a mechanism for this creative introduction of ideas. We also thought there was an opportunity to create buzz in the market place, but I think it really boils down to wanting to new and different things and not to be so inhibited by your process. That’s the essence of it.

Hiroshi, what’s your exact involvement in the HTM project?

Hiroshi Fujiwara: My role is to make our ideas applicable to the worlds of street or fashion. Tinker comes up with innovative ideas and presents them with remarkable determination. Mark delivers the overall vision for the project, while still contributing his unique perspective as it relates to culture and design.

HTM shows that when independent minds collaborate, the results can be quite profound. We each are active in our fields. Tinker works on his own projects, Mark is busy running the company, and I get to do what I like as a freelancer. But when we come together, we’re able to create something that often has great influence.

How has HTM changed over the years, if any at all?

HF: When I met Mark for the first or second time, before he became the CEO, he asked me, “If you were to do something with Nike, what would it be?” I answered that I wanted to help elevate certain models. I thought it would be nice to have a program where we could customize and update shoes, rather than just changing colors.

At the beginning, HTM became an opportunity to add a sense of luxury to sneakers, starting with that Air Force 1. There were not so many Air Force 1 collaborations before the first HTM shoe. Also, this was a time when luxury sneakers were not so common. These days, rather than updating what has already been around, HTM is more about releasing new ideas for the first time.

What do you recall about the first HTM shoe, the Nike HTM Air Force 1?

MP: As I recall, we wanted to take a classic icon and make it absolutely stunning. With HTM, there aren’t really any constraints. We can use the best materials at our disposal because we’re not usually creating something that’s produced in great numbers. So for the Air Force 1, we wanted to make a premium version by using incredibly high-end leather. And instead of athletic color blocking, we emphasized the classic lines of the shoe with contrast stitching.

You guys recently have done a handful of Kobe Bryant sneakers. Is there a reason why you decided to work with Kobe and not LeBron James or Kevin Durant?

TH: We look across the landscape at Nike, and there are so many projects with so many athletes, but sometimes people pop up and it seems appropriate. Kobe is someone that we’ve all met. I’ve worked with Kobe and Mark Parker knows him quite well. It seemed like if you were to add another letter into the “HTM” with a K on the end, he would fit right in, because he has a lot of good ideas himself. So it seemed to be a natural extension of the HTM sub-brand to do something for an athlete. He had a unique way to look at how we introduce products. Kobe’s great. He’s so cool to work with, he’s such a smart guy, he’s very stylish, thinks about everything, gives us time—all the things you want in a design partner.

Does he ever give you critiques or feedback on the HTM versions of his signature shoe?

TH: Yeah, I know he got a close look at the three different pairs of the shoe. I didn’t sit down with him on my shoe, but it’s OK because we talk on the phone. The reality is that he’s very involved, he’s like Michael Jordan in that way: He wants to be involved, he likes design, and he’s one of those athletes that will give you time. He’s quite involved in everything that’s associated with him.

Hiroshi, what’s the biggest difference between doing fragment and HTM?

HF: HTM is more about releasing new ideas for the first time. With HTM, I get visibility into Mark and Tinker’s ideas, thoughts and inspirations from different moments and times, including those of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. So it’s a fascinating project. It’s also quite powerful. We have the freedom to push forward whatever we are interested in. Once we decide to do something, we can start moving right away.

The Sock Dart was re-released in the past couple years. A lot of people would say that it was ahead of its time when you designed it over a decade ago, Tinker. Did you ever think it would take 10 years for it to become a big thing?

TH: I was disappointed when the brand didn’t get behind that shoe very much. Part of the problem was that it was so different. It was difficult for a lot of people to recognize it as a new idea. I was bummed that we only made a few thousand pairs. They sold and then the project went away for awhile. Yet, what’s great about Nike is that that someone else took the mantle of knitting and built off the foundation of the Sock Dart, and we ended up with Flyknit. That opened up the door for the Sock Dart to come back out, because people are now open minded about shoes that are built completely differently and have a different feel and look. We all have to wait for our time in the sun, and that particular shoe had a 10-year wait.

When you’re creating these offbeat projects, do you think you’re taking a gamble if the public is to going receive them in a positive way?

TH: For me, I think everything is going to work great. I’m like an idea machine, and the other people are like me and come up with ideas to do the same thing. We’re always pushing to do the unexpected, the new, and the different. If we were the only decision makers in this company, it probably would have gone out of business 20 years ago [laughs]. There are people who are more conservative about what they do, and what makes Nike, or any other successful company, great is the balance. So I’m pushing, and there are other people who are pushing in our advanced design group and other categories, then there are other folks who are saying, “Whoa, slow down. How can we sell something that no one understands or is too different?” There’s a balance we’re trying to strike as a company, and I get a little disappointed that people don’t always see it my way. But, on the other hand, I’ve had a few successes as well getting some things through. We have to roll with those punches. In the end, it’s working nicely, I’d say.

In 2012, Nike introduced Flyknit through HTM. What are your memories of that project?

MP: We could see the amazing potential right away. It was clear that we were rewriting the rules of performance engineering. When we saw the leap that could be made by using Flyknit instead of cut and sew, it was like comparing airbrush to collage. It’s so precise. Now we could micro-engineer whatever solution we wanted—support, flexibility, or breathability—by manipulating both the yarns and the stitch patterns.

In 2012, we delivered the first performance HTM product—the Flyknit Racer—and it made the podium in its first test at the U.S. Olympic Trials marathon. It was the beginning of an innovation that has transformed our whole company, and what’s so exciting is that, even now, we are just starting to uncover the infinite possibilities of Flyknit.

Last year you guys did the MTM Air Jordan 1, did you ever think you were going to do an HTM Jordan?

TH: It’s a separate thing, but the idea of a sub-brand is the same. This one might have been my idea, and I remember talking to Mark Parker and saying, “Hey, we can invite other people into our sub-brand.” And who better to invite into your sub-brand than Michael Jordan? We changed the letters a little bit, made it MTM, and invited Michael into the process. He got to see how we operate as a sub-section of Nike and Jordan Brand. It worked out great and Michael loved the project, he loved being a part of it. So we might do that again, we don’t really want to tip our hat about how we’re going to do these things. I think part of the fun of it is to keep people guessing a little bit, and maybe we’ll do an Obama “MTO” [laughs]. We’re open for other collaborators and making decisions amongst a small group of people and using ideas from those same people. There could be more fun stuff to come.

by Cwe | Feb 27, 2016 | Creative Process, Fashion

Prada goes vagabonding. “It’s such a difficult period; we don’t know who we are or who we want to be.” This was Miuccia Prada, backstage, trying to explain herself after a tour de force of a collection, while being divebombed by well-wishers and journalists trawling for a crumb of enlightenment like so many starving sea gulls: Give us depth, or give us damask.

She did both. For while Mrs. Prada was talking generally, about the messy state of things and female identity, from power players to protesters and the current (non)unified state of Europe, she could also have been referring to the fashion world and its current debate (and growing divisions) over whether the whole system needs to change. Whether clothes should be sold as soon as they are shown (a growing impulse in New York and London), or whether things are fine just as they are (the position of many in Milan and Paris — except that Prada itself is offering two bags from the runway for immediate sale online and in select stores).

Mrs. Prada didn’t have an answer, but her show suggested a place to start: Consider how we got here. “It’s a collage of a woman,” she said. “All the parts of her, good and bad.”

That meant barely laced corsets over tough military greatcoats and fur-trimmed Prince of Wales check capes twinned with argyle tights; sailor semiology in the form of hats and anchors; and shirts and dresses and skirts printed with work commissioned from the artist Christophe Chemin. Mr. Chemin also collaborated with Prada on its men’s show last month, a clear antecedent, as is increasingly true in many collections from Gucci to Burberry. Here, he created a cycle of the seasons inspired by the French Revolutionary calendar, in which each month was named for a woman, according to the brand’s collection notes.

“Every piece says something,” Mrs. Prada said, be it about sex or strength or travel or heritage. They added up to a historical narrative, complete with some strange and awkward moments — where did the trousers go? “We couldn’t make them work,” Mrs. Prada said, “so we just took them out” — pieced together through the aesthetic perspective of a different lens.

Think of it as the examined wardrobe. It wasn’t always comfortable (neither, in hindsight, are all our choices), but it was convincing.

Vanessa Friedman The New York Times

by Cwe | Jan 26, 2016 | Creative Process, Design, Print

Start by looking beyond fashion, drawing inspiration from art, photography, branding and graphic design before we look to street style, catwalks and tradeshows.

Here are five key points I bear in mind when building or designing a print collection:

Create a mood board

This will help consolidate an idea and communicate a clear message. Four strong images are sometimes better than 40. It’s always good to consider your muse – who will wear this print? What season is it for? What market is it for? It’s good practice to answer these questions before you begin the design process.

Don’t simply rely on Tumblr

The influx of readily available information and Tumblr accounts full of recurring images means we have to look beyond the Internet for inspiration. Of course, use blogs and Instagram but also look to exhibitions, upcoming films and emerging designers from street art to illustration, to inform trends.

Consider perennial favorites

Nothing is new. Many core trends re-appear time and time again and evolve through seasons. Think about how to update perennial trends such as camouflage, animal skins and festival florals. Look to new techniques, effects and styles to refresh these repeating themes.

Colour

Pick key colours from your inspiration and pair with popping accents and subtler shades to craft a balanced palette. Colour can really make or break a print so it’s a good idea to try three colourways of a design before you make your final decision.

Experiment with scale

Scale often gets forgotten when you’re focusing on the details of a print design. Experimenting with scale can be the most impactful and effective way of renewing a time-honored favourite. Is it a micro-scale ditsy or a strikingly oversized repeat? You can use CAD (Computer-aided design) drawings to quickly visualise the scale on the end product.