by Cwe | Sep 23, 2016 | Creative Process, Fashion

Alexander Fury is becoming my favorite fashion writer. Here he takes on appropiation of cultures for designer’s collections. What is inspiration and when are you crossing the lines? And how did the sensitivity changed throughout the past decades:

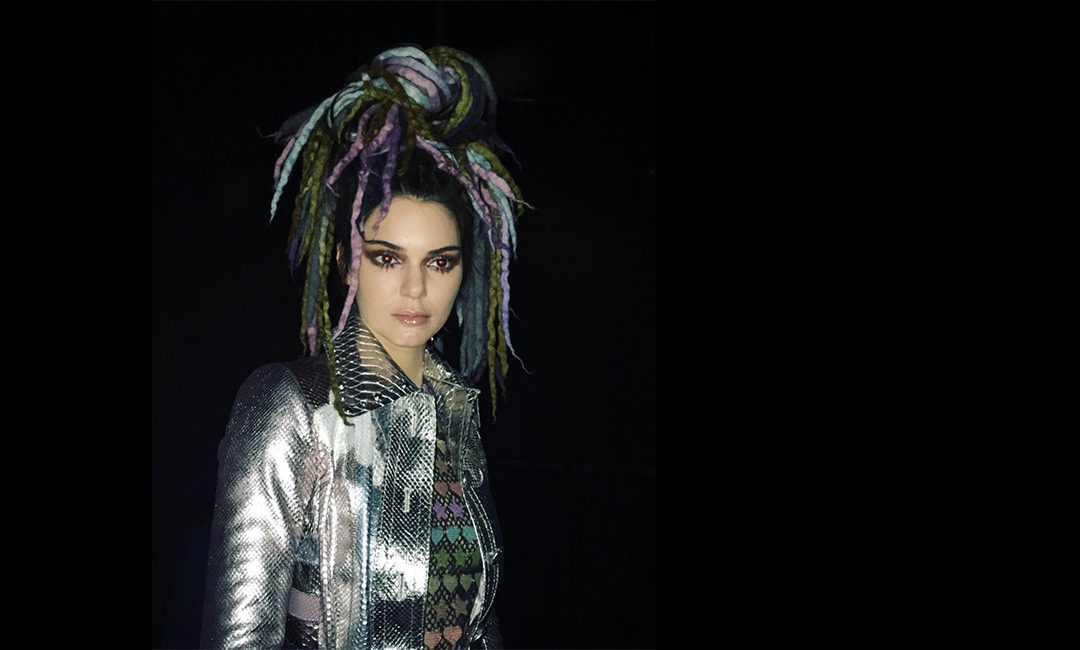

Despite the fashion calendar shifting continents and an entire fashion week unfolding in the interim (London’s five-day schedule ended yesterday evening), attention is still being drawn back to New York; namely, to Marc Jacobs. Last Thursday afternoon, Jacobs unveiled his spring/summer 2017 show, to generally positive critical reviews — and a social media brouhaha. The focus was the models’ hair, braided into multicolored dreadlocks inspired by the transgender filmmaker Lana Wachowski and sourced online. The designer was subsequently accused of cultural appropriation, of lifting influences from black culture and showing them on a cast of predominantly white models. Jacobs was rapidly tried and sentenced by a public jury; a fusillade of comments rained down on Instagram and Twitter. Jacobs responded, first by “justifying” his actions and then, after that engendered further criticism, apologizing for the justification, and for any offense caused. The story had already leapt from the fashion pages: Time ran a piece, as did many other general-interest publications.

The thing that struck me was, ironically, how very Marc Jacobs all this feels. Jacobs’s distinct talent is to, somehow, divine the moods of the moment and compress them into 10-minute fashion shows. Often, the mood is confined to the aesthetic, to a particular fashion buzz about to chime with the populace: Fetish! Leopard! Denim! Sometimes, he digs deeper. His spring/summer 1993 grunge collection for former employer Perry Ellis nailed an emerging cultural moment, coupled to fashion but also encompassing music and a general “slacker” feel. It was presented two years before Kevin Smith’s “Clerks,” but, as that film did, represented a break with not only the aesthetics but the social mores and values of the ’80s. It was, maybe, the true start of the ’90s. (F.Y.I., it got Jacobs fired.)

This collection isn’t quite as seminal — but when it comes to nailing the mood of the time in which we live, it’s bang-on. Today is a moment of uncertainty, a moment teetering on tenterhooks, of walking on eggshells. Jacobs collection wasn’t intended to be controversial: “cyberpunk, cyber-goth, street kids, club kids, couture,” were the references Jacobs’ stylist, Katie Grand, reeled off to me 48 hours before the show. If anything, Jacobs’s appropriation was of the already-appropriated, the dreadlocks sported by the aforementioned style subsects. The reaction to it, however, epitomizes a media landscape dominated by 21st-century terminology like “trigger warning” and “micro-aggression.”

Fashion has been “borrowing” from other cultures for decades. Elsa Schiaparelli based her upturned shoulders, the ones that set the silhouette for the ’30s and ’40s, on the costumes of Balinese dancers. Yves Saint Laurent pillaged the Steppes and the Far East. Almost everyone’s turned to Japan at some point — or an idea of Japan, like those laid out by Edward Said’s 1978 book “Orientalism,” and which are applicable to collections by designers as diverse as Paul Poiret, Yves Saint Laurent and Giorgio Armani.

But at what point did appropriation become inappropriate? When did designers start being called out on their picture-postcard odes to foreign lands and people — what’s changed?

I wonder if those collections will be reassessed, by subsequent generations, with the judgment we apply to blackface — of decidedly inappropriate cultural colonialism, antiquated and uncomfortable to watch. “The point of academic analysis is not to criticize, but to reveal the contradictions, to possibly reveal the flaws that are symptomatic of their time,” Evans points out. “It tells you something about the period, that we need to learn.”

What should we learn from our period? Perhaps that every look will be analyzed, and criticized, and that the criticism will be vocal via a permanently plugged-in, Wi-Fi world. That, regardless of intent or stated inspiration, every nuance and reference could be second-guessed. That it’s not easy to riff on other cultures without someone feeling ripped off, and that the offended are quick to take to social media to voice their disdain. That’s a good thing, potentially — it makes designers stop and think about other cultures, hopefully to gain a better understanding of their references, which probably makes their designs better, or at least more intelligent. There’s also a simpler lesson: that you’ll never please all of the people all of the time. But it’s good to try to understand their point of view.

by Cwe | Sep 14, 2016 | Creative Process, Designers, Fashion, Technology, Trends

In “The Extraordinary Process,” nine designers — Patrik Schumacher, Ms. Hadid’s partner at Zaha Hadid Architects; Peter Do; Phoebe English; Iris van Herpen; Stephen Jones; Krystyna Kozhoma; Nasir Mazhar; Minimaforms and XO — consider how fashion and design are affected by new technologies and collaborations.

Pieces designed by Patrik Schumacher for an exhibition inspired by the work of the architect Zaha Hadid, who died in March. Credit Damian Griffiths/Courtesy of Maison Maison Non

The architect Zaha Hadid, who died unexpectedly in March, was known for her flamboyant and very personal fashion sense. While her architectural practice become famous for large-scale, soaring structures, like the opera house in Guangzhou, China, or the Maxxi museum in Rome, it has embraced fashion, jewelry design and household items with a similar fervor and spirit of innovation. “In terms of form, all our projects — architecture, fashion and furniture — interest me equally,” Ms. Hadid said in a 2015 interview.

Here are edited extracts from the conversations:

Patrik Schumacher

I teach at the design lab at the Architectural Association, and we have been working on texture-like materials to use in construction. But in our architectural designs, we have done origami-style curved folding. It’s a world of forms, more than anything, and then you seek customization. For the exhibition, I’ve designed a three-piece suit using neoprene and mesh because I want that elasticity and comfort. Instead of buttons, there are zippers, and the way the suit is constructed and layered is unconventional. At the same time, it is still recognizably a suit, elegant and very wearable, and you could go jogging after dinner without changing.

Krystyna Kozhoma

A design by Krystyna Kozhoma. Credit Damian Griffiths/Maison Maison Non

I saw a video about curved folding in architecture, and it inspired me to create clothes with programmed shapes. So I’ve embedded clear bars in the fabric of a jacket and trousers to create a structured shape. I worked with an engineer, and there was no pattern cutting; the clothes were made by a computer program. That’s still limited in fashion and mostly used for 3-D printing. This is a translation from architecture to fashion, and the shapes and fluidity of the lines show how much my work is inspired by Zaha. She took a lot of inspiration from nature but then computerized it. What’s interesting is that if the embedded material reacted to light, or temperature, you could make the garment a smart one. That’s the next project.

Iris van Herpen

From Iris van Herpen’s Lucid collection. Credit Iris Van Herpen Lucid Collection/AW16

I’m showing a dress from my Lucid collection that is built of thousands of small transparent pieces. They create a bubble or halo around the body, and around the dress we have built an installation of optical light feeds from thin, transparent sheets that bend the light. From each angle, you see the garment in a different perspective and with a sense of movement. For me, that reflects the future: uncertain and personal to each individual. I think Zaha’s work is a beautiful balance between the futuristic and the organic, and I tried to stay true to that balance.

Peter Do

Peter Do made a unisex coat, sweaters and boots. Credit Damian Griffiths/Courtesy of Maison Maison Non

I was thinking about minimizing one’s wardrobe and functionality, so I used a single yarn, made from cellophane, woven in many different ways, and made a unisex coat, sweaters and boots. Each looks different because of the way it is fabricated and layered. I worked with Stoll, a knitwear company in New York who make incredible knitting machines that can do extraordinary things. In the future, I think they’ll be much more simple to use, and I had this idea that everyone could have a Stoll machine at home, download your patterns, choose your yarns and your garment would be knitted by the time you got home from work.

Phoebe English

Phoebe English’s piece. Credit Damian Griffiths/Courtesy of Maison Maison Non

I realized, when I got the brief, that I felt a bit frightened of the future. So I designed an enclosure or private space, a kind of safety shell. It’s constructed from a heavily smocked textile with very closely packed pleating. It’s half calico and half plastic, so it has both a rawness and a sheen. I’ve always admired the shapes and forms of Zaha’s work; there is something about that fluid line that I feel has a strong feminine aesthetic. That has been a big influence on me. When people envisage future design, it often looks hard and polished and technological. I wanted something with a different vision.

Stephen Jones

Photo

Stephen Jones’s design. Credit Damian Griffiths/Courtesy of Maison Maison Non

Zaha was a client of mine, and I felt we had a similar approach. She made forms, constructions which relate to people, and I do the same thing as a milliner, but put them on people’s heads. She once gave me a sketch of a vortex that she had used as a design element in a restaurant in Sapporo, and I took that as my inspiration. My tribute to her is a red, spinning vortex hat over a stool she designed and a cushion made from the Issey Miyake pleated fabric she always wore. For me, it’s an idea of energy, speed and transformation. I love the idea that in the future you’ll put a magical hat on, and it will make you feel a certain way.

by Cwe | Aug 28, 2016 | Creative Process, Design, Handbags

Design Meeting with 邱光平 in Chengdu.

Do you know how to pony like bony maroney

Do you know how to twist, well it goes like this, it

goes like this

Baby mash potato, do the alligator, do the alligator

And you twist the twister like your baby sister

I want your baby sister, give me your baby sister, dig

your baby sister

Rise up on her knees, do the sweet pea, do the sweet

pee pee,

Roll down on her back, got to lose control, got to lose

control,

Got to lose control and then you take control,

Then you’re rolled down on your back and you like it

like that,

Like it like that, like it like that, like it like

that,

Then you do the watusi, yeah do the watusi

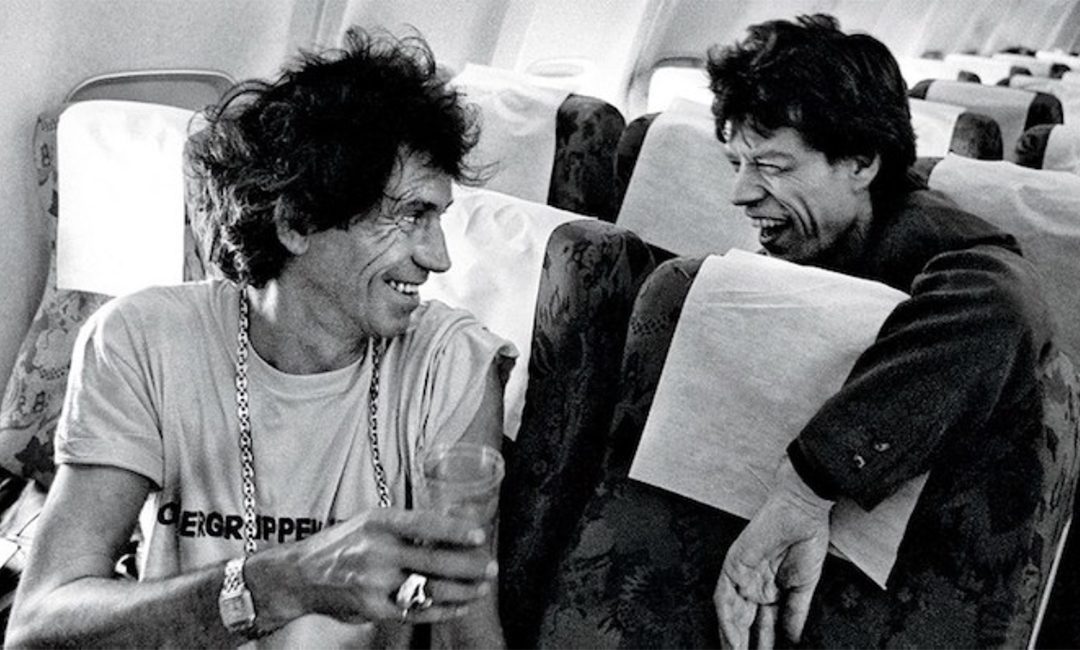

by Cwe | Jul 13, 2016 | Celebrity, Creative Process, Creativity, Music

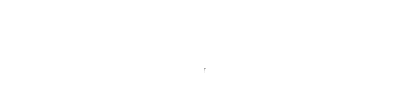

Creativity, success, reinvention according to the Rolling Stones by James Altucher.

Mick Jagger fooled around with Keith Richards’ girlfriend. I wouldn’t be able to work with someone after that.

But maybe that’s why I’m an author. And not a rockstar.

The Rolling Stones became a new band every 5-7 years. They were “perpetual amateurs.”

That’s one of the keys to staying alive as an artist.

Or as an entrepreneur.

Or staying alive at all… “Remain the same but different.”

And be “open to influence,” Rich Cohen said. He wrote “The Sun & The Moon & The Rolling Stones,” an incredible book about the greatest rock ‘n’ roll band of all time, fate, creation, sex, influence and the art of reinventing yourself.

It was “the gig of a century:” touring with The Rolling Stones the summer of ‘94. Then Rich worked with Mick Jagger on the HBO series “Vinyl.”

But this story isn’t just about The Rolling Stones. It’s about creation, corruption and reinvention.

And the 9 ways you can reinvent yourself today:

1. Use your frustration

Rich became an artist out of anger. So did The Rolling Stones.

Rich’s father told him “blood-soaked bedtime stories” about the Jewish gangs of New York.

“There was this idea where I grew up that if you were Jewish, certain possibilities were foreclosed to you.”

He wrote “Tough Jews,” which heavily influenced the movie “Goodfellas,” and later led to more mob media like “Boardwalk Empire” and “The Sopranos.”

“Everything’s connected,” he said.

Frustration is fuel for reinvention. Someone without problems won’t create. Instead, they’ll idly count money. And wonder where their smile went.

Frustration wrote, “I can’t get no satisfaction,” the song that Mick Jagger says “prevented us from being just another good band with a nice run.”

“There was this whole soap opera… A rock band not only has this great blues base. They also have someone who’s addicted to something, and they’ve got this weird relationship between the lead singer and the guitar player. They love and hate each other,” Rich said. “And they’re like brothers.”

They worked their tensions through the music.

And Rich worked his through writing.

“I was interested in this idea of expanding what it means to be Jewish and making it more complete,” he said. “And also the stories are so great.”

He wrote “Sweet and Low” about his grandfather who invented the famously pink sugar packet out of desperation.

He saw a single-sided stereotype about Jews. A good stereotype, “but still a stereotype.”

You have to find your frustrations. And invent from annoyance.

2. Remain open

Mick Jagger went to dance clubs in his fifties.

“We’d go out and have dinner or whatever. And then you go home. But he would go out… mostly because he wanted to see what was making kids dance.”

“A lot it’s driven by what goes on inside a person,” Rich said.

But it’s also about:

1 “remaining open”

2 “and willing to be astonished by new things“

That’s influence. And inspiration.

I read to write.

One of my favorite books, “Jesus’ Son,” is the drug addict’s version of “Huckleberry Finn.”

You have to take in the landscape. Find out what else’s out there. And combine it with your ideas.

The Rolling Stones “started out as record collectors with the best taste.”

Look at what you love and then…

3. Ignore the myth of age and wisdom.

Rich’s dad is 83. And he (generally) only accepts opinions from people his age.

“Listen,” Rich tells his dad, “you’re gonna run out of people you can listen to because there’s only a couple million of them left on the whole planet.”

“If something’s huge and people love it, I want to read it to see what the hell’s going on.”

If you hold your breath against change, your mind will cripple with your body.

Look at people 20 years younger than you.

See what they’re doing and…

4. Rip off the best stuff

OR…

6. Be the anti-

Everybody knew they’d get “love from The Beatles and sex from The Rolling Stones.”

5. Liberate yourself

I put step six before five.

You don’t have to go in order. Rules are only as real as you make them. And the more you follow them, the less freedom and control you have over your life.

The best way to change your life is to reinvent yourself. That’s why everyone dreams of doing something drastic. Quitting their job, flying across the country or getting a sex change. You’re finally listening to yourself. It’s liberating.

Start small.

Do your morning routine in reverse. Change the temperature of your shower. Order dessert first. I don’t care.

Just give yourself permission to stop holding yourself accountable to the little habits.

Because no one cares about that. Not even you…

7. Chase something

Jagger would go to Lennon’s apartment on the Upper East Side. Leave him notes. And rarely hear back.

“Everybody has someone they want to hang out with who won’t hang out with them,” Rich said.

Reinvention is a mystery.

“A lot of it is driven by anger and openness. And being willing to be astonished by new things. One good way to keep reinventing yourself is not to be too successful, actually,” Rich said.

You have to “feel like you’re chasing something all the time… [something] you can get but just can’t quite get.”

I asked Rich, “Do you think John Lennon liked Mick Jagger?”

It doesn’t seem like John Lennon would like Mick Jagger.

Their relationship is weird.

8. Go from fan to imitator to original

“A lot of musicians starts with a song,” Rich said. “The Rolling Stones started with an idea.”

But they needed help transitioning from fans to imitators to originals.

So Lennon and McCartney wrote The Rolling Stones’ first “original” song.

9. Never stop re-inventing

In the beginning, they ripped off blues bands.

“And then in the ‘70s, they kind of turn and get into reggae. And it’s a whole new thing”

“Then Mick Jagger goes to Studio 54 and discovers disco. And suddenly they have this album that’s like a fight between disco and the blues caught on vinyl and that’s ‘Some Girls.’”

Rich says that was their last great album. Because they stopped reinventing themselves. It’s the death of every good artist. Your skill withers, your brain atrophies and your fans move on.

by Cwe | Jun 10, 2016 | Creative Process, Creativity, Design, Designers

I am engaged in the creation of artificial arrangements that would bring out the real emotions. Whether publishing a pop-culture magazine in my early twenties in Munich, shooting fashion internationally later on, or designing and producing fashion accessories in New York and Asia, I try to tune on to the finest aesthetic frequencies on the air during right now. A musical teenager, a media addict, a mind alterations engineer, a Bikram body, a blender chef, a bicycle driver, and a curiosity victim, I am learning how to juggle. Toptal seems to be the right fit. I look forward to join the Toptal Freelance Visual Designers Community.

by Cwe | Jun 1, 2016 | Art, Creative Process

Gaia Repossi is the daughter of the master jeweler Alberto Repossi. Gaia was appointed creative director and designer of all Repossi collections, turning the label into the most wanted fine jewelry brand of the moment and casually earning her master’s in archaeology and anthropology along the way. She is talking about her creative process, why pink diamonds are so precious, and how opulence can be redefined in the 21st century.

It always starts with a pattern—a shape, a sculpture, a drawing, a grid. It can be the way some kid in Ethiopia wears an earring, or a line of a Frank Lloyd Wright house. My references come from contemporary art, and the effects of metal within modern sculpture and architecture. I take inspiration from the works of Alexander Calder, Cy Twombly, Franz West, Richard Serra, and Le Corbusier, as well as from the brutalist, minimalist, and Bauhaus movements. I like blending and pushing the boundaries between architecture and traditional high jewelry techniques. I also like working through systems. So one idea can be done in infinite variations. If we take the Berbere series as an example, it comes in more than 1,500 variations: one row, two rows, three rows, seven rows. Thin row, thick row, colors, pavé. I like the idea of infinite possibilities.